Darts and bitter beer

The most commonly registered trademarks are images, words or combinations of both. This makes sense: the name of your product or service and your logo are the most important recognition points for consumers. As a company, you want to avoid these being copied by competitors.

But you can also protect other ‘signs’ as trademarks. This makes sense too, given that other elements also help consumers recognise that your company is behind a certain product or service

Non-traditional trademarks

Did you know, for example, that the position of a specific element on a product can be registered as a ‘position mark’? Think of the red label on the pockets of a pair of LEVI’S trousers. In itself a trivial piece of fabric, but instantly recognised because it’s always in the same place. That is why it was protected as a position mark.

Every sign that serves as a recognition point for the consumer can be registered as a trademark. Think of holograms, sounds, colours, etc. You can then prevent someone else from using similar signs. We call these ‘non-traditional trademarks’.

Scent marks

Of all the non-traditional brands, scent marks are probably the most difficult to get registered. This is due to the criteria that non-traditional trademarks must meet to complete the registration process.

In particular, certain conditions apply when submitting the trademark application: how do you represent the sign you want to regsiter in the application? The conditions that apply in the EU were defined in the Sieckmann decision of 2002:

Firstly, the sign must be presented clearly, precisely and objectively. In addition, the representation must be easily accessible, intelligible and self-contained, so that everyone can find what exactly is protected. A chemical formula, for example, is not comprehensible to everyone. Non-chemists will not be able to define the scent represented by a chemical formula.

Finally, the representation must also be durable and objective. This means that an odour sample does not qualify as a representation, as the odour may dissipate or change over time and the specific odour of a substance is subjective.

In 2017, the rules for the representation of marks were relaxed. The former requirement that they be ‘graphically representable’ was removed. As a result, you can now, for example, upload an mp3 of a jingle in your EU trademark application. This makes sense, as almost anyone who has access to the trademark register can play an mp3.

For fragrances, there is not yet a standard way of presenting which is clear, precise, complete, easily accessible, durable and objective. We occasionally hear about machines being developed that can mimic scents, but these are not up to scratch yet and are certainly not easily accessible.

So although we are seeing more and more holograms, position marks, etc. appearing in the trademark registers, it will be some time before scent marks appear in the registers.

Actually, we should put it differently: before scent marks will appear in the registers again. Of course, trademark registrations already existed before the Sieckmann case of 2002. Some national trademark offices were less strict at the time, which led to the registration of a few scent trademarks in the 1990s.

Darts

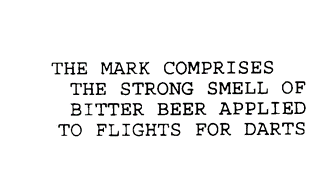

And so we come to darts: one of the few remaining scent brands in Europe is a British brand for darts. In 1994, Unicorn Products managed to register ‘the strong smell of bitter beer’ as a trademark for darts. The specific scent released when opening their packaging was a recognition point for their flights and this was considered a registrable mark.

The description of the scent mark in the 1994 trademark registration

Trademark registration can be renewed every ten years, and Unicorn Products has consistently done so. As a result, they now own a rather unique right, at least until 2024: a scent mark registration.

Troll’s summons gone wrong

Copyright trolls

Copyright trolls are companies that obtain copyrights from many photographers and other authors, then use software to scan the Internet for infringements. Once they find a website on which the image has been posted without permission, they try to scare the operator and demand exorbitantly high sums. As all of this happens automatically, they often make mistakes and there isn’t even any infringement.

This way of working seems to pay off. Some companies are frightened into paying the excessively high costs. Others, without seeking professional advice, pick up the pen themselves, making false concessions or (even more often) failing to address the legally most important points. By doing so, they give the trolls a free pass in court.

Of course, there are also cases where there simply is infringement. It is then often appropriate to pay a fee to the author. However, the fee must be set at a correct level. A fee of thousands of euros (usually) isn’t.

Rage against the Permission Machine

In a recent judgment, the Corporate Court of Ghent, backed by the EU Court of Justice, disagrees with such practices. It is unacceptable that financial objectives take precedence over the effective protection of copyrights.

The plaintiff, Permission Machine BV, uses automated search engines to search for infringements of its clients’ copyrights. It then systematically sends a license offer to the (alleged) infringers. The payment of a license fee is clearly the goal, while the actual cessation of the infringement seems unimportant.

For example, in 2019, the Defendant, Kortom VZW (a non-profit organization), received a communication from Permission Machine: Kortom had used 3 photos in its newsletter on government communications, without permission. Permission Machine put the npo in default. As an accomplished copyright troll, of course, it also offers a license for no less than 848.00 euros.

Kortom’s newsletter is always removed after a month. When Permission Machine asks for 848.00 euro in license fees, the images have already been removed from the website. Kortom refuses to pay the amounts. After sending several reminders, Permission Machine sues the ngo in summary proceedings in March 2021. Permission Machine demands that the alleged copyright infringements cease and that Kortom pays the costs of the proceedings (1,440.00 euros). Such a verdict will then be used to scare future victims.

Abuse

The judge, however, disagrees with Permission Machine’s way of working. He refers to recent case law of the European Court of Justice. The Court was asked whether a company such as Permission Machine can rely on all the instruments of enforcement that authors themselves can rely on. For example: a claim to stop copyright infringement. To this the Court answered with a very expansive “yes, but”. This because the general right to use these instruments is limited in the case of abuse.

A person who holds a copyright, but does not exploit it himself and only claims damages based on this right, can only use the instruments and procedures if it is judged that this does not constitute abuse. It is up to the national courts to determine whether there is abuse, but the Court provides a number of example circumstances.

Specifically, it is suggested that a judge look at the method of operation and the objectives. A modus operandi where the focus is always on financial compensation and not on actually stopping infringement may indicate abuse.

Therefore, the Corporate Court of Ghent now decided that Permission Machine is indeed abusing the cessation tool. The purpose is financial gain and not the effective protection of copyrights. The judge deduced this from the following elements:

- The cessation of infringement is not a priority in the communication to Kortom, where Permission Machine demands the payment of a fee. It even mentions that removal will not suffice to escape payment of the fee.

- Permission Machine makes no effort to prove that the images are indeed copyrighted and that the protection of these rights is entrusted to them.

- The requested fees seem arbitrarily determined. They are then compounded with unproven costs.

- There was a long period of time between the demands for payment and the final claim for cessation. This makes it appear that this claim is intended more as a punishment for non-payment than as a measure of actual copyright protection and cessation of infringement.

- The claim was filed unannounced.

- The damage from the use of the images is very limited. The newsletter is temporarily online. The website has a limited audience.

It is clear to the judge that the instrument of claim to cessation is misused in this case. Accordingly, the claim is judged unfounded.

Conclusion

The European and Ghent rulings undoubtedly have consequences for the practices of copyright trolls in Belgium. Threatening a summons and claiming damages to force a payment will become a less effective means of pressure. Of course, it remains important to respond appropriately to the communications of these shrewd creatures companies.

The image in the header is part of a work by John Bauer. John Bauer died in 1918, so his work is in the public domain.

Written by Barbara Verstraeten & Thierry Van Ransbeeck

Did you receive a ‘Notice of absence of formal requirements’ from the EUIPO?

Before publishing your EU trademark application, the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) will examine if the formal requirements are met.

If you are located outside of the European Economic Area, the deficiency will usually be a lack of local representation. The EUIPO’s notice will read along the lines of:

“No representative has been appointed. According to Article 119(2) EUTMR, natural or legal persons not having either their domicile or their principal place of business or a real and effective industrial or commercial establishment in the European Economic Area must be represented before the Office in all proceedings other than filing an application for a European Union trade mark. The representative appointed must be from within the European Economic Area. Article 120(1) EUTMR sets out who may act as a representative before the Office. A list of representatives can be found through eSearch on the Office website.”

While companies from any country can file an EU trademark application, only those established in the EEA can do so without a local representative.

As registered EUIPO Trademark & Design Attorneys, we can help you solve this type of deficiency. For instance, the above issue can be solved by us registering at the EUIPO as the representative for your application. In most cases, the cost for this action is only € 70,00 per trademark application.

If you don’t remedy formal deficiencies, the EUIPO will refuse your trademark application. You will not get your filing fees refunded.

The deadline to remedy the deficiency will be mentioned on the EUIPO’s notice. It’s usually 2 months. So don’t hesitate, and contact us for assistance.